Papers

I bring clowning to the workshops as it gives so much pleasure and laughter to the children.

Many of them have had such difficult lives; it seems only right that they have a chance for a good laugh and some fun. As they have seen little live performance I start the workshop with a short routine where there is plenty of audience involvement. I then show them a few comic skits based around the park bench. Trying to read someone else’s newspaper, and dealing with a stranger falling asleep on your shoulder. It reminds these children, (as it does to all children that I have taught), of Mr Bean, and it is an opportunity to introduce them to the silent world of Charlie Chaplin. I invite them to try out the routines.

The challenge for the students is to let themselves to be made a fool off, allowing the audience to laugh at their vulnerability. In devising the routines they also have to work co-operatively together, where their normal playground attitude is, maybe, to try and dominate. I tell them it is the only time they have to be stupid and silly enough to fall for the joke! After the initial shock, they are good at picking up on these ideas and as participants have a go the routines, we discover the odd one who has that intuitive sense of comedic timing.

Clowning is of course about making other people laugh. In a workshop situation where participants are searching for creative ideas that may be humorous, they can discover other talents. These children can dance and sing.

They have a joy in dancing to hip-hop music, and most are very capable of following the dance steps. I introduce the idea of a clown being in a dance troupe attempting to dance correctly, but making plenty of mistakes and causing havoc to the rest of his fellow dancers. They love the idea and are happy to try.

In introducing the clown that sings we find one small girl who is a very good singer. She is able and confident enough to lead the others in many Nepalese children songs that everyone seems to know. It great to see them all join in and then others also have a go at leading. It is a wonderful way of bringing the group together.

The drama exercises have really brought a stronger sense of focus with the group, allowing me to introduce slap-stick. That is clown fights. Including pulling hair, pulling ears and the face slap. Given their difficult lives, both Anne and I are surprised how well they co-operate with each other. They start to add the slap stick to their role play with the school teacher, student routine being the most popular. Having the teacher being told off by the student gives them a lot of joy. It is allowing this sense of naughtiness, within a theatrical frame work that makes clowning for children so challenging and yet so much fun

Many of them have had such difficult lives; it seems only right that they have a chance for a good laugh and some fun. As they have seen little live performance I start the workshop with a short routine where there is plenty of audience involvement. I then show them a few comic skits based around the park bench. Trying to read someone else’s newspaper, and dealing with a stranger falling asleep on your shoulder. It reminds these children, (as it does to all children that I have taught), of Mr Bean, and it is an opportunity to introduce them to the silent world of Charlie Chaplin. I invite them to try out the routines.

The challenge for the students is to let themselves to be made a fool off, allowing the audience to laugh at their vulnerability. In devising the routines they also have to work co-operatively together, where their normal playground attitude is, maybe, to try and dominate. I tell them it is the only time they have to be stupid and silly enough to fall for the joke! After the initial shock, they are good at picking up on these ideas and as participants have a go the routines, we discover the odd one who has that intuitive sense of comedic timing.

Clowning is of course about making other people laugh. In a workshop situation where participants are searching for creative ideas that may be humorous, they can discover other talents. These children can dance and sing.

They have a joy in dancing to hip-hop music, and most are very capable of following the dance steps. I introduce the idea of a clown being in a dance troupe attempting to dance correctly, but making plenty of mistakes and causing havoc to the rest of his fellow dancers. They love the idea and are happy to try.

In introducing the clown that sings we find one small girl who is a very good singer. She is able and confident enough to lead the others in many Nepalese children songs that everyone seems to know. It great to see them all join in and then others also have a go at leading. It is a wonderful way of bringing the group together.

The drama exercises have really brought a stronger sense of focus with the group, allowing me to introduce slap-stick. That is clown fights. Including pulling hair, pulling ears and the face slap. Given their difficult lives, both Anne and I are surprised how well they co-operate with each other. They start to add the slap stick to their role play with the school teacher, student routine being the most popular. Having the teacher being told off by the student gives them a lot of joy. It is allowing this sense of naughtiness, within a theatrical frame work that makes clowning for children so challenging and yet so much fun

Training Notes from Professional Development Workshops 2011 and 2012 in the City of Casey

Training Notes.

Workshop Co-facilitation. Who you could be co-facilitating with? Other artists, psychologists, councillors or teachers.

What are some of the purposes of co- facilitation? What is to be gained? What are the different forms of co-facilitation? Working with another. Consider the roles each is taking in a group.

Active /Passive Supportive / Obstructive. Involved /Disengaged. Neutral.

Where are the tensions, creative or personality? Relating to your co-facilitator. What role is each of you taking?

Where are the compromises? Is one person dominating (all or some of the time?)

Working with your co-facilitator, when do you take the lead when do you follow?

Observation of self.

How does my contribution affect others?

The skills of co-facilitating

Preparation Negotiation Developing a theme Guiding the group. Benefits and joys of co-facilitation.

Workshop Co-facilitation. Who you could be co-facilitating with? Other artists, psychologists, councillors or teachers.

What are some of the purposes of co- facilitation? What is to be gained? What are the different forms of co-facilitation? Working with another. Consider the roles each is taking in a group.

Active /Passive Supportive / Obstructive. Involved /Disengaged. Neutral.

Where are the tensions, creative or personality? Relating to your co-facilitator. What role is each of you taking?

Where are the compromises? Is one person dominating (all or some of the time?)

Working with your co-facilitator, when do you take the lead when do you follow?

Observation of self.

How does my contribution affect others?

The skills of co-facilitating

Preparation Negotiation Developing a theme Guiding the group. Benefits and joys of co-facilitation.

Engaging participants from diverse cultural backgrounds

Warm up games.

The games we play include the following

name games

Storytelling and dramatizing the story.

In devising the story in this workshop we aim to reach a deeper appreciation of the lives of people from different backgrounds and discover what we have in common.

To start the story telling project we create structure. For this workshops, that structure starts with a skeleton of a story. We ask participants to add to it.

Our story

A mat catches your eye as you

go into the room.

Light enters the room through

a gap in a curtain.

You notice the atmosphere is

scented and you are alerted by a distant

noise.

You see a vessel.

As you rest your gaze upon it,

you recall the story of how you both came to be together in that

room.

In helping participants to develop the story we

ask specific questions that provoke the imagination.

In doing so we ask participants to be inspired by their own lived

experiences. We evoke the senses to

inspire ideas.

Where are you? Where is the room?

How do you feel emotionally about being in the space?

What is the eye seeing?

What are you smelling?

How is the sense of touch activated?

What sounds are you hearing?

Discussion on working with people from culturally diverse backgrounds

Warm up games.

The games we play include the following

name games

Storytelling and dramatizing the story.

In devising the story in this workshop we aim to reach a deeper appreciation of the lives of people from different backgrounds and discover what we have in common.

To start the story telling project we create structure. For this workshops, that structure starts with a skeleton of a story. We ask participants to add to it.

Our story

A mat catches your eye as you

go into the room.

Light enters the room through

a gap in a curtain.

You notice the atmosphere is

scented and you are alerted by a distant

noise.

You see a vessel.

As you rest your gaze upon it,

you recall the story of how you both came to be together in that

room.

In helping participants to develop the story we

ask specific questions that provoke the imagination.

In doing so we ask participants to be inspired by their own lived

experiences. We evoke the senses to

inspire ideas.

Where are you? Where is the room?

How do you feel emotionally about being in the space?

What is the eye seeing?

What are you smelling?

How is the sense of touch activated?

What sounds are you hearing?

Discussion on working with people from culturally diverse backgrounds

As Kenneth Tynan wrote of Beckett’s tramps after the London premiere of Waiting

for Godot in 1955: “Were we not in the theatre, we should, like them, be clowning and quarreling, aimlessly bickering and aimlessly making up – all, as one of them says, ‘to give the impression that we exist.’ ”

Over half a century after they first appeared on stage, the tramps, Pozzo and Lucky,

once again delight in this strongly poisonous drama. Samuel Beckett's Godot

has been generously crafted and remains for all ages, an obscure meandering in

its psychological, philosophical and aesthetic layers; in its climax without a

climax and its beginning without a beginning. Rather it has been compared by the

likes of Herbert Blau; "to a piece of jazz music, to which one must listen for

whatever one may find in it" – the cries along with the laughter,

simultaneously intertwined with significance, perhaps?

With all that in mind, I would be foolish to get myself involved in all the round table political

and ideological qualms about its meanings, futility; of Beckett's

intensely sufficient subconscious. In its expression, symbolic to absurdity and

with no specific hope, we had to wait for "Godot" – and continue to wait.

I will say one thing though about the audiences' outcome: a clear, agreed upon parallel response to what contradicts our

Australian way of life. We could not dismiss the treatment of the working class

other than something strange and lacking in humanity: but perhaps that was," the

divorce between man and life that constitutes the feeling of absurdity". Albert Camus, French philosopher, talked largely about the loss of meaning in life and of shattered dreams: the thick of the play.

The two tramps waiting for Godot near a tree spending idle time, to see the evening out, conversed and compared

songs, understood each other's inadequacies through poetry and achieved their

haunting struggle through vaudeville. One of them expressed this with, "we're

all born mad, some remain so".

Later in the night they were disturbed by passers by Pozzo and his slave Lucky twice in the play. Here we witnessed the contradictions of society, equality and personality and could not help but laugh and cringe at some of the prescribed analogy. Beckett simply said in one interview that the play was about interaction, physical interaction between different organisms, perhaps between masters and slaves, the lonely and the story tellers; all with something to gain.

The out of harmony tramps played by John Flaus and Bruce Kerr, were just enough to keep that ridiculous senseless genius awake.

The sitting, the standing, the sleeping, the brown colours and of course carrots and boots revolved in a room where everything was talked about. Languages from English to quietly whispered gibberish were stirred and stammered and screamed

and vexed. The Lordly arrogant Pozzo played by Peter Finlay, wore his character through the outside of his costume. His voice

trembling the first two rows, at least, and his pantomime silhouette, haunted

even the most eager of sadists. Lucky played by Alex Pinder, perfected for us a sorrow and the story became surrounded by his

frozen mime. His mute presence fell onto and above and within a declamation, a

visual storm dipped in ghastly screeches and hollow screams that moved the room,

better still shook our insides. The mystery of Godot and the interaction that the tramps were waiting for was played by Vivian

Schmieder – a little boy who would come down some flights of stairs and declare where the play was at; or where our dreaming was at.

If you were lucky enough as I was you would have noticed the eyes of the actors. There were glistening eyes all over the stage, piercing projections. The concentration was immensely alive with compliments and truth and at the same time ragged Chaplin physicality. You could smell the decay of things old; of things forgotten. Old doors opening and closing, a rope stretched across the floor and the sounds and dim lights of hopelessness.

If you love the theatre, and if you want to know about life and about clowns and about anger and hypocrisy – Godot has to be your path to knowledge. On the other hand if you can see reason and symbolism behind hats and whips, carrots, radishes and turnips, then Godot will purposefully enslave you with smells and texture that you yourself can paint once you leave.

A paper I gave at the 2011 ADSA Conference at

Monash University on June 28th.

My name is Jyoti Mukherjee or Jyotirindra Nath MUKABADHAI. Some of you may know me by my stage name Alex Pinder

I was born in University College London and grew up for the first 12 years of my life and mainly in London Oxford and Cambridge.

This paper is about how I have tried and, I suppose am still trying to find a place in an acting profession that is hard enough to get work in.

I settled in Sydney to at 14 with my parents my Indian father Soumyen Mukherjee and English mother who was born Dorothy Pinder.

At school I found it was in the theatre where I shone. I wanted to be an actor, After I left school in 1976 I auditioned for NIDA got close to getting in and was told to come back in a year or so. In the mean time I went to the Ensemble Studios which was part of The Ensemble Theatre run by the Hayes Gordon who was a very tough task master. He was from the Stanislavski, New York influenced school.

You did not have to audition to get in to the Ensemble Studios, Hayes expected most people to drop out as most of us would not be suited to the toughness of a very difficult profession. Along with the rigours of the learning the craft of acting he encouraged and insisted we working with a sense of integrity, That is trying to recreate life type situations with a sense of accuracy and honesty. In other words, don’t go cheap laughs

I have to admit I found the first months there extremely difficult and I was almost on the verge of dropping out , when I got a phone call to come an audition for a in one of The Ensemble’s professional shows, The English playwright Trevor Griffiths Comedians, that Hayes was going to be directing.

I could not understand why he would choose me. I felt I had not done anything in class to stand out. That was until I was the handed the script and was asked to read for the role of Mr Patel an Indian migrant to England. Well you could have knocked me over with a feather. Oh my God Hayes thinks I am Indian. Now I did not feel Indian at all, as much as one could feel a nationality, I thought of myself as English. I grew up on egg and chips and my favour the football team was Tottenham Hotspurs.

As a kid I had often been to my father ‘s child hood home in Kolkata, we spent some time in Delhi before coming to Australia could understand some Bengali ,but was really treated as the English relative. Should I tell Hayes how I feel that maybe he has got the wrong person t. I was not really Indian and he should find some else. Well of course, I took the role.

It is also about how I tried to represent characters of an Indian background on stage and screen with a sense of integrity and if I have to say “Please accept my humble apologies” and keep my dignity intact.

The Play Comedians was about, the dangers of comedy and laughing at those that different and less fortunate than ourselves. Long before political correctness came in, a very provocative play, of its time a great learning experience for an actor to be working on. I was given a wonderful experience of a 12 week season for someone so young and inexperienced.

Hayes used to give each a through line or main motivation for the play. For Mr Patel it was to belong. Well I could relate to that, being a relatively new migrant and just entering a new profession I desperately wanted to be part of. I also had my say in the design and the look of my costume, especially when I was told by the designer; it could be good to wear a turban, to help make it clear where you could be from. In the pursuit of working with some integrity I gave a definite no to the turban. And what I realised that there was very little understanding or knowledge of the Indian sub-continent and all its cultures.

It led to 18 months in about 1978, I was the offered role of Ahmed in Alex Bubo’s well known play Norm and Ahmed, written and first produced in 1968 to tour Tasmania for The Tasmanian Theatre in Education Company about to become The Salamanca Theatre Co.

For those who don’t know Norm and Ahmed is a fifty minute play where an Australian ex digger meets a young Pakistani student late one night on the streets of Sydney.

Norm’s approach to Ahmed is sometimes threatening sometimes very friendly and through it we get to know these two characters. Just when we think they are going to become friends Norm violently attacks Ahmed and calls him a fucking buong which is the last line of the play that in 1968 got the actor saying the line in La Mama production and in the Brisbane production arrested, for saying fucking, saying bung was not an offence.

Buzo wrote a classic. A strong portrayal of two archetypes. In Norm the lonely ex-digger, who is a widower and is traumatised by his experiences in the 2nd world war, he fought at Tobruk, his father was at Gallipoli, feeling very insecure about the future that is left to him Ahmed is the idealist young student , studying in Australia , also lonely but at least a very optimistic future.

The language of Norm is full old Australian phrases, and Ahmed speaks in a very formal English that he was taught from a text book in Pakistan.

The trap for actors is to fall into playing one dimensional caricatures. This was especially so for Ahmed as he had less lines and , being written in Australia the emphasis of the play was on motivations of Norm.

And of course my recent training wanted me to do it with certain integrity. And I did have the line, Please accept my humble apologies. For a young actor this line felt all wrong. Surely no one would talk like that, and with the accent, it would surely sound like Peter Sellers in The Party. How would I do it? May be just under play; even mumble it, sort of like an Indian version of Marlon Brando mumbling. Well that rubbish, you have to go with pleading and passion of the line. In doing I started to learn about my being Indian, the passion and the emotion of that part of my upbringing.

In the many after show discussions of the play I have witnessed over the years, the discussion is mainly on Norm, except when there is a multi- cultural audience, and the question is always why did Ahmed stay especially when it seems at times he was in danger? When Australian audiences were asked,

Why would Ahmed stay, the answer always surprised me? “OH he just being polite it's part of his culture. “ Polite is the sub- continent culture? I don’t think so. That would just make him a card board cut-out caricature.

Yes he may be being polite but he was also interested in Norm and his life, he says he is interested in human behaviour and people less fortunate than himself. And it makes Ahmed much more interesting to play and a more rounded character.

I have been involved in productions of Norm and Ahmed over the years. In fact in the late 70s and early 80s it was performed a number of times in Australia and there not many actors of an Indian Pakistani background , so there was quite a bit of work.

Among my peers was praise at me getting work but also the sneers? Oh, you only got the job because you were Indian, or they could get past the amusement of a Pakistani accent, which still happens when you play Indian roles.

I was asked to do a film version of it for Film Australia. Alex Buzo came on set a number times during the filming, and we discussed , I thought he jokingly how would it be if Norm and Ahmed was set in the 1980s. Well the Ahmed character would probably be Vietnamese. In the early 90s I think I did see a production called Norman and Tuan at La Mama where Norman was a Vietnam vet and Tuan was from Vietnam. The structure is the same but the dialogue has of course changed

In 2010 the writer Graham Pitts contacted me and talked passionately about the violence against Indian students that had been happening at the time. What could we do about it? He wanted to write a play about it there and then He did not have the time so through his company Many Moons he brought the writes to Norm and Ahmed, I directed it. I got Peter Finlay to play Norm and I was spoilt for choice in getting an Ahmed. How times have changed.

Through Melbourne Student Theatre I found Kevin Ponniah, an Australian resident of Tamil Malaysian background, and having also been educated in Singapore.

For a modern audience I wondered if the text going to seem too old fashioned, do we have to modernise it. If we did modernise the characters would be so different, especially Ahmed. He would surely now be a more confident consumer of education, and able to hold his ground against Norm

I think the piece is so well written that we did not change a word. Kevin found similar problems playing Ahmed as I did, but in making him interested in Norm he gave a very rich performance, and even was able to send up the clichéd Indian character. The piece was very well received proving again what a gem of play it is.

Yes the role of Ahmed did give me an entry into the profession, which I really enjoy, but was I ever going to part of its mainstream. I was asked by an agent to change my name, I probably stupidly agreed. I took on my mother’s maiden name. I use to get work on fringe, still do, and in the 1980s in subsided community and regional theatre which had little or nothing to with my Indian background.

In film and television I have been put for roles of characters with an Indian background and still I AM trying, sometimes failing, sometimes succeeding in making them credible giving them integrity. It is always a problem when the lines are written as he has just stepped off the boat speaking very poor English. Or the director says, can you do it like Peter Sellers in The Party, and can you shake your head from side to side.

I have often played supporting role to overseas Indian actors, who had the lead mainly based in England some of them very well known. They told me it was hard for them to play anything except the Indian roles.

I also decided to get more training and in the mid- eighties went to L’Ecole Jacques Lecoq in Paris. This gave me more strings to my bow and an ability to create my own work and confidence in directing and teaching. This also helped me keep in work, as there were not enough roles for actors with my type of back ground.

Part of Lecoq’s philosophy was that everyone has a place in the theatre it is up to you to find where you belong. That word again belong, I am still trying to find where I belong. Not that I am complaining the journey been fun at times exciting and it is always on going.

Also as a teacher I am really enjoy teaching groups that on the outer of their societies. Teaching clowning and mime to street kids in India or tribal communities in North East Thailand or indigenous schools in The Northern Territory, enabling students to use using drama and the arts to open their imagination and as a way into education.

As a director I try and cast in an interesting way. The best way I did was in Singapore at La Salle College of Arts, where in The Comedy of Errors I had to cast two sets of twins from a pool of Indian

On the positive side it the profession has taught me to understand more and celebrate my Indian heritage which of course is an endless task. I find strange that when cast in an Indian role some people feel I am an expert on India .

I would like to be able to perform more often on the main-stages and on screen playing a wider variety of roles. That is why I cannot be at the conference this week. I am in Queensland filming a role in an American TV series Terra Nova. The interesting point about this series is that all main actors are from overseas, but not all American. It seems to be a culturally diverse cast. The guest role I have is that of a scientist, and there is no mention of the character being from India or Pakistan or anywhere. It is such a relief.

There needs to be more stories told on our stages and screens especially on the main stages reflecting times the culturally diverse nature of the Australian community so we All feel we belong.

From Bangkok to Benalla Feb to April

2011

I have just completed a stint in directing student actors

at GRADA TAFE an acting course based in Benalla Victoria. It sure was a

change after spending seven months in Bangkok I had eight very enthusiastic students to direct in scenes and monologues they had chosen from the catalogue of plays from the 20th century. So scenes that were chosen included, Tennessee Williams "Street Car Named Desire" and The Glass Menagerie (my favourite), Arthur Miller’s The Crucible, to Dario Fo’s Accidental Death of an Anachist, and Australian plays such as Michael Gow’s Away and Nick Enright’s Blackrock. We titled the evening of scenes and monologues Love and Other Catastrophes.

For many of the students this was their first experience on stage, and I must admit I felt very proud of the work they had achieved

Directing Grada students in a scene from The Glass Menagerie by Tennessee Williams.

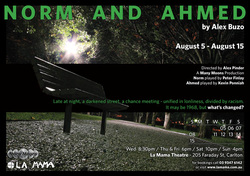

Full review of Norm and Ahmed.

Directed by Alex Pinder. La Mama, Melbourne, until August 15 2010.

Anyone who wants to know anything about playwriting, directing, acting and designing has until August 15 to get themselves to La Mama and see this brilliant account of Mr Buzo’s (a national treasure, surely) faultless first play.

Written in 1969 (which today is somehow almost too confronting to accept), it was notoriously the subject of a prosecution for obscenity – not, as La Mama’s Artistic Director Liz Jones pointed out (in her wonderful and emotional postscript to the performance) for the use of the word “boong”, but for the use of the word “fucking”. It was here, at La Mama, that Norm and Ahmed was first produced – and as a gentleman in the audience pointed out before the drawing of the famous ‘La Mama Raffle’: “Have the police been notified?” Norm and Ahmed also holds the La Mama record for the most re-stagings of a play at the theatre – with this Many Moons production being the fifth.

Mr Buzo’s script is all lean, theatrical muscle and Mr Pinder’s direction of it is absolutely beautiful in its stark and pure textual complicity. Peter Finlay (Norm) and Kevin Ponniah (Ahmed) deliver two of the most accomplished, tour de force performances in recent memory, and one has no choice but to forgive them their opening night nerves in front of a capacity house – bursting at the seams – for this rare and historic occasion.

In ‘Norm’, Mr Buzo somehow miraculously – and entirely – encapsulates a complex national identity including its deep-seated anxieties about the very essence of what it means to be different. From ‘Norm’s’ razor-sharp commentary about the “perverts” in the bushes to his moving reminiscence of his late wife ‘Beryl’ and his experiences as a soldier in the war – Norm is a monstrously illuminating creation. That people like him still exist, is cause for serious contemplation – and it is in his holding up of the cracked mirror where we, reluctantly, may find something of our own prejudices reflected, that marks Mr Buzo as a truly astonishing playwright. That it’s all done and dusted in under an hour makes him a master.

The tendency to fall into caricature in the performance of these two roles is never far from likely – such is the perilous line between stereotype and archetype around which great writers of great characters for the stage dance. In Mr Finlay’s hands, however, the immensely complex ‘Norm’ is in a craftsman’s hands. At times, through a most incredible vocal and emotional range, it was never entirely clear if Norm was going to kiss Ahmed or kill him. Norm’s vulnerability, his fear, his hatred and his quintessential Australian suspicion are all beautifully realised in this stunning performance. For anyone even remotely interested in the art of acting, this is what it looks and feels like. As Ahmed, Mr Ponniah is all wide-eyed wonderment and naivety – layered with a sense of genuine eagerness to be accepted by his marvelously engaging new-found friend. Mr Ponniah’s complete command of Mr Buzo’s dialogue was superb – and the audience loved it. The shouts and cheers at the end of the performance, with curtain calls which one sensed could have gone on all night, were entirely well-deserved.

Nothing, however, can prepare you for the final moment in Norm and Ahmed – and the woman sitting three seats away from me almost leaping from her seat and screaming “No!”, was the entire measure of this electric night in the theatre. It is compulsory viewing. Go.

Geoffrey Williams

Anyone who wants to know anything about playwriting, directing, acting and designing has until August 15 to get themselves to La Mama and see this brilliant account of Mr Buzo’s (a national treasure, surely) faultless first play.

Written in 1969 (which today is somehow almost too confronting to accept), it was notoriously the subject of a prosecution for obscenity – not, as La Mama’s Artistic Director Liz Jones pointed out (in her wonderful and emotional postscript to the performance) for the use of the word “boong”, but for the use of the word “fucking”. It was here, at La Mama, that Norm and Ahmed was first produced – and as a gentleman in the audience pointed out before the drawing of the famous ‘La Mama Raffle’: “Have the police been notified?” Norm and Ahmed also holds the La Mama record for the most re-stagings of a play at the theatre – with this Many Moons production being the fifth.

Mr Buzo’s script is all lean, theatrical muscle and Mr Pinder’s direction of it is absolutely beautiful in its stark and pure textual complicity. Peter Finlay (Norm) and Kevin Ponniah (Ahmed) deliver two of the most accomplished, tour de force performances in recent memory, and one has no choice but to forgive them their opening night nerves in front of a capacity house – bursting at the seams – for this rare and historic occasion.

In ‘Norm’, Mr Buzo somehow miraculously – and entirely – encapsulates a complex national identity including its deep-seated anxieties about the very essence of what it means to be different. From ‘Norm’s’ razor-sharp commentary about the “perverts” in the bushes to his moving reminiscence of his late wife ‘Beryl’ and his experiences as a soldier in the war – Norm is a monstrously illuminating creation. That people like him still exist, is cause for serious contemplation – and it is in his holding up of the cracked mirror where we, reluctantly, may find something of our own prejudices reflected, that marks Mr Buzo as a truly astonishing playwright. That it’s all done and dusted in under an hour makes him a master.

The tendency to fall into caricature in the performance of these two roles is never far from likely – such is the perilous line between stereotype and archetype around which great writers of great characters for the stage dance. In Mr Finlay’s hands, however, the immensely complex ‘Norm’ is in a craftsman’s hands. At times, through a most incredible vocal and emotional range, it was never entirely clear if Norm was going to kiss Ahmed or kill him. Norm’s vulnerability, his fear, his hatred and his quintessential Australian suspicion are all beautifully realised in this stunning performance. For anyone even remotely interested in the art of acting, this is what it looks and feels like. As Ahmed, Mr Ponniah is all wide-eyed wonderment and naivety – layered with a sense of genuine eagerness to be accepted by his marvelously engaging new-found friend. Mr Ponniah’s complete command of Mr Buzo’s dialogue was superb – and the audience loved it. The shouts and cheers at the end of the performance, with curtain calls which one sensed could have gone on all night, were entirely well-deserved.

Nothing, however, can prepare you for the final moment in Norm and Ahmed – and the woman sitting three seats away from me almost leaping from her seat and screaming “No!”, was the entire measure of this electric night in the theatre. It is compulsory viewing. Go.

Geoffrey Williams